Ferromagnetism: Thouless, Nagaoka and Tasaki

This note originates from discussion with Patrick Ledwith, Margarita Davydova, Rahul Sahay, Saranesh Prembabu and Jiaqi Cai.

Nagaoka Ferromagnetism

The statement of Nagaoka ferromagnetism[1] is the following. Consider the Hubbard model:

\[H = -t\sum_{\left\langle i,j \right\rangle\sigma}c^\dagger_{i\sigma}c_{j\sigma}+U\sum_{i}n_{i\uparrow}n_{i\downarrow}\]We know through the superexchange argument that when \(U\gg t\) at half filling one get an antiferromagnetic exchange \(J\sim t^2/U\):

\[H_{eff}=J\sum_{\left\langle i,j \right\rangle}\vec{S}_i\cdot\vec{S}_j.\]Although the system is antiferromagnetic at half filling, at fillings slightly less than one half - more precisely, one hole less than half filling - Nagaoka proved that the system, with infinite interaction \(U\) and certain conditions on the lattice, exhibit ferromagnetism. We note that in the infinite \(U\) limit the antiferromagnetic exchange is exactly zero, so probably this result shouldn't be so surprising.

His treatment is rather complicated, so here we resort to the treatment of Tasaki[2]. Below we state the theorem.

Generalized Nagaoka Theorem (Tasaki). Consider an \(N\)-site Hubbard model

\[H = -\sum_{i,j,\sigma}t_{ij}c^\dagger_{i\sigma}c_{j\sigma}+U\sum_{i}n_{i\uparrow}n_{i\downarrow}\]where \(U\to\infty\) and \(t_{ij}\leq 0\). Then, if the number of electrons \(N_e=N-1\) and the lattice satisfies the connectivity condition (defined below), the ground state is ferromagnetic.

Proof: The \(U\to\infty\) constraint forbids double occupancy. We can thus label the permitted states in the Hilbert space as

\[\ket{i,\vec{\sigma}} = (-1)^i c^\dagger_{1\sigma_1}\dots c^\dagger_{(i-1)\sigma_{i-1}}c^\dagger_{(i+1)\sigma_{i+1}}\dots c^\dagger_{N\sigma_N}\ket{0}\]Basically \(i\) labels where the hole is and \(\vec{\sigma}\) labels the spin configuration on the sites other than \(i\). Now the Hamiltonian only has the kinetic term. We note that the kinetic term - when acting on the basis states \(\ket{i,\vec{\sigma}}\), can only move the hole due to the on site Hubbard \(U\). We note that the hole feels the opposite hopping compared to the electron; basically, if we use the particle hole transformation \(c\to d^\dagger\), \(d\to c^\dagger\), the kinetic part of the Hamiltonian changes sign:

\[-\sum_{i,j,\sigma}t_{ij}c^\dagger_{i\sigma}c_{j\sigma}=\sum_{i,j,\sigma}t_{ij}d^\dagger_{i\sigma}d_{j\sigma}+\text{const.}\]This will be important in the discussion later.

We study symmetries of the Hamiltonian; the only symmetry is the \(SU(2)\) symmetry that rotates the spin. Let's take the subspace corresponding to angular momentum \(S_z\). The connectivity condition states that, for all \(S_z\), the Hamiltonian projected to the subspace is irreducible (in the Perron-Frobenius sense): there does not exist a permutation matrix that further block diagonalizes the Hamiltonian. This means that, for \(\ket{i,\vec{\sigma}}\) and \(\ket{j,\vec{\tau}}\) belonging to the same block \(S_z\), there exists a chain of states \(\ket{a_i,\vec{\sigma}_i}\) such that \(\left\langle i,\vec{\sigma}|H|a_1,\vec{\sigma}_1 \right\rangle,\left\langle a_1,\vec{\sigma}_1|H|a_2,\vec{\sigma}_2 \right\rangle,\dots,\left\langle a_m,\vec{\sigma}_m|H|j,\vec{\tau} \right\rangle\) are all nonzero. Since the Hamiltonian is basically just a hopping matrix for holes, these matrix elements will be equal to \(t_{ij}\), the hopping amplitude for the hole. Physically, this statement means that because of the hole hopping around, the system can go through all possible spin configurations.

As we have hinted in the previous paragraph, we will now apply the Perron-Frobenius theorem to \(-H_{S_z}\), the negative of the Hamiltonian projected to the block \(S_z\). Given that \(-H_{S_z}\) is irreducible, the ground state is unique in each \(S_z\) sector.

We will now prove that the ferromagnets are ground states. Since there is one ferromagnet in each \(S_z\) ground state, they are necessarily the only ground states. Given any state \(\ket{\psi}=\sum_{i,\vec{\sigma}}\psi_{i,\vec{\sigma}}\ket{i,\vec{\sigma}}\) (the wavefunction can be taken to be real), consider the state \(\ket{\phi}=\sum_{i}\phi_i\ket{i,(\uparrow)}\) where \(\phi_i=\sqrt{\sum_{\vec{\sigma}}|\psi_{i,\vec{\sigma}}|^2}\) and \((\uparrow)\) means a sequence of up spins. We prove that the ferromagnetic state \(\ket{\phi}\) must have lower energy than \(\ket{\psi}\).

\[\begin{aligned}\left\langle \psi|H|\psi \right\rangle &=\sum_{i,j,\vec{\sigma},\vec{\tau}}\psi_{i,\vec{\sigma}}\psi_{j,\vec{\tau}}\left\langle j,\vec{\tau}|H|i,\vec{\sigma} \right\rangle\\ &\geq \sum_{ij}t_{ij}\left(\sum_{\sigma,\tau}|\psi_{i,\vec{\sigma}}\psi_{j,\vec{\tau}}|\right)\\ &\geq \sum_{ij}t_{ij}\sqrt{\left(\sum_{\sigma}|\psi_{i,\vec{\sigma}}|^2\right)}\sqrt{\left(\sum_{\tau}|\psi_{j,\vec{\tau}}|^2\right)}\\ &=\sum_{ij}t_{ij}\phi_i\phi_j=\left\langle \phi|H|\phi \right\rangle \end{aligned}\]Thus, the ferromagnets are ground states; given the uniqueness of the ground states, they are the only ground states.

Several remarks are in order on the stability of the theorem, as one may find that this result seems artificial and singular. Several constraints need to be realized simultaneously: sign of hopping (the important constraint, as we will demonstrate in the following sections), infinite Hubbard \(U\) and the exact doping of one hole. We comment on each of the aspects below.

Sign of hoppings. Note that the sign of electron hopping amplitudes is generally not well defined; one can define an arbitrary gauge in real space to completely stir up the signs of hopping amplitudes. In particular, for bipartite lattices with only inter-lattice hopping, one can flip the sign of the wavefunctions only in one of the sublattices to change the sign of the hopping amplitudes. We just need a gauge choice where all hopping amplitudes are negative for holes for Nagaoka ferromagnetism to hold.

Infinite \(U\). Of course, realistically \(U\) can't be infinitely large. Is a finite \(U\) ferromagnetism expected? The answer is generally yes, given that the only ground states are ferromagnets. A physical argument as we shall see below is the following. The ferromagnet will be stabilized by the kinetic energy of the itinerant hole, and thus the relevant energy scale will be the kinetic energy scale \(t\), whereas the antiferromagnetism is stabilized by the superexchange \(t^2/U\). Thus when \(U\) is very large, the ferromagnetism still wins.

Doping one hole. Whether the ferromagnetic state will be the ground state when we dope two holes into the system is already debatable. Consider artificially dividing the system into two halves, with one hole sitting in the center of each. By Nagaoka ferromagnetism, each side of the system will be ferromagnetic. However, when we recall that we still have to couple the two systems together on the boundary, it is not unimaginable that the entire system will be a singlet, something like one side completely pointing up and the other side completely pointing down. This does not prevent the observation of ferromagnetism: in general, the splitting between the fully polarized state and this singlet state will be exponentially small in system size, and a small magnetic field will completely polarize the state.

The proof of Nagaoka theorem is quite formal. Below, we shall distill the essence of Nagaoka ferromagnetism through Tasaki's excellent toy model[3], which was already known to Thouless in 1965[4].

Itinerant Hole Causes Ferromagnetic Exchange

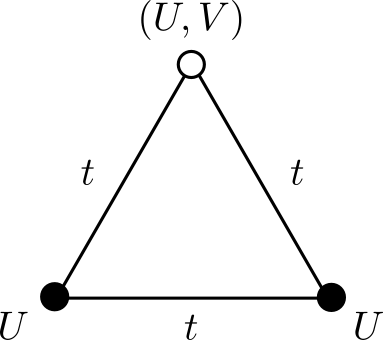

Consider the following simplistic setup which follows the spirit of Thouless. In a three site Hubbard model with two electrons shown in the figure, let us artificially suppose that we add a huge on site potential \(V\) to one of the sites so that the hole in the system gets pinned to that site. We study the effective spin-spin interaction in the remaining sites.

The Hamiltonian is

\[H=-t\sum_{\left\langle i,j \right\rangle\sigma}c^\dagger_{i\sigma}c_{j\sigma}+U\sum_{i}n_{i\uparrow}n_{i\downarrow}+V n_0\]; we don't fix the sign of \(t\), and we assume that \(t\ll V\ll U\).

Apart from the usual superexchange antiferromagnetic exchange \(J_{S}\sim t^2/U\), we also have the following exchange due to "hole pushing spins around":

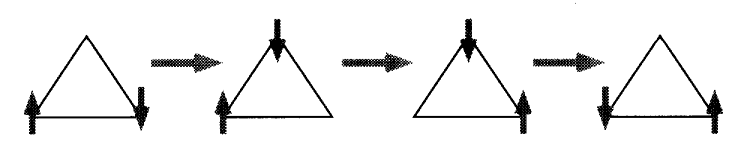

This figure is taken conveniently from Tasaki's review[5]. This virtual process, generally called "ring exchange", will contribute to the exchange interaction

\[J_R \sim \frac{t^3}{V^2}\]with the sign not fixed. Now we fix the sign.

From the general Schrieffer Wolff transformation, in a hopping model of fermions or bosons, where the low energy Hilbert space and the high energy Hilbert space has energy difference \(\Delta\), the loop exchange of length \(N\) will in general contribute an exchange of

\[J\sim \left(\prod_{i=1}^N (-t_i)\right) \left(-\frac{1}{\Delta}\right)^{N-1}\eta^{N-1-N_h}\]where \(-t_i\) are the hopping amplitudes of the \(i\)-th hopping process for particles, and \(\eta=1\) for bosons and \(-1\) for fermions, and \(N_h\) is equal to the number of holes present in the exchange process. We note that \(-\eta t_i\) are the hopping amplitudes for the holes. Simple examples are: \(J\sim t^2/U\) for fermionic superexchange (expected), \(J\sim -t^2/U\) for bosonic superexchange (surprising, and more discussions later). In this case \(\eta=-1\) and \(N=3\), where \(t\) is taken to be negative. Thus the total sign in this case is positive in \(t^3/V^2\), which itself is negative. One can in general check that when \(\eta t_i<0\) for all hoppings, \(J\) is negative - in accordance with Nagaoka ferromagnetism.

And thus in total, we expect the effect spin Hamiltonian to behave as

\[H_{eff}\sim \left(t^2/U+\frac{t^3}{V^2}\right)\vec{S}_1\cdot\vec{S}_2\]As expected, \(U\to\infty\), the antiferromagnetic exchange is \(0\); since \(t<0\), the exchange coupling is ferromagnetic. As we can see, this ring exchange mechanism - which symbolizes the mobility of the hole - makes the system ferromagnetic. In short, we can summarize the lesson we learned as "in an electronic system where holes feel negative hopping amplitudes, localized holes will create a ferromagnetic environment around it".

The Nagaoka ferromagnetism can be easily extended through this argument by taking the \(V\to 0\) limit. Although this limit feels singular, it is because we are no longer able to write down a local exchange interaction because the electrons can move across the system. Particularly, the connectivity condition enables the hole to visit every single site in the lattice, bringing its ferromagnetic aura everywhere. In some sense, one should replace \(V\) by the kinetic energy of the hole - proportional to \(t\) - so that the ferromagnetic energy scale will be proportional to \(t\), the hopping.

Non-bipartite Lattices, Particle-Hole Asymmetry, and Particle Statistics

We notice that the statement of Nagaoka theorem does not care about whether the system is made up of fermions or hard-core bosons; it just needs the holes to feel a negative hopping. But the "parent state" of Nagaoka ferromagnetism - the half-filled state - is drastically different for bosons and fermions: for bosons, as we alluded to in the previous paragraph, the state is a ferromagnet, whereas for fermions it is an antiferromagnet. Of course, on bipartite lattices, the ferromagnet is exactly equivalent to the antiferromagnet by flipping spins on one of the sublattices. Thus, in one dimensions for the nearest neighbor hopping Hubbard model, we can't tell the difference between fermions and bosons, as is made apparent by the bosonization procedure.

These two phases are genuinely different on non-bipartite lattices, such as the triangular lattice. Notably, on the triangular lattice the fermions don't enjoy the particle-hole symmetry; \(t\to -t\) changes the single particle spectrum.

Thus, let's consider the normal triangular Hubbard model where \(t>0\), both for bosons and fermions. For bosons, the Nagaoka criteria holds (holes have the same hopping as particles, which is negative); thus at doping \(\nu=1-\epsilon\), we get ferromagnets. The same holds for the particle doped case: if we slightly dope the system with doublons, the will also hop with negative hoppings. (One can particle hole transform the whole system and map it to the hole doped case.) Thus, on both sides of the doping, we get ferromagnetism.

However the same thing isn't true for fermions. If we dope holes to a half filled triangular lattice, the holes feel positive hoppings and the Nagaoka ferromagnetism fails; there is no way to correct it to fully negative hoppings, because the phase a particle feels when it goes through a plaquette is physical. On the other hand, if we slighly dope doublons into the system, they do feel negative hoppings, and thus we get Nagaoka type ferromagnetism at \(\nu=1+\epsilon\).

The bosons are particle hole symmetric whereas the fermions are not: in this case, the hopping breaks particle hole symmetry. On a similar but possibly unrelated note, there is a more fundamental particle hole symmetry - particle hole transforming only one species of spin. In that case, the bosons will still be symmetric, whereas the electron interactions will flip sign. It is this symmetry being broken that leads to strongly correlated physics rather than Fermi liquid behavior[6]. This result is completely general and does not depend on the lattice geometry.

More analytic results in similar non-bipartite lattices such as the Kagome lattice is pioneered by Mielke[7]; one can basically understand the flat band of Kagome lattice as many copies of the three-site toy model discussed in the previous section. Mielke also constructed some analytically solvable models that exhibit ferromagnetism in 1D, such as the Mielke-Tasaki chain[8].

References

| [1] | Y. Nagaoka, Ferromagnetism in a Narrow, Almost Half-Filled s-Band (1966). DOI |

| [2] | H. Tasaki, Extension of Nagaoka’s theorem on the large-U Hubbard model (1989). DOI |

| [3] | H. Tasaki, The Hubbard Model: Introduction and Selected Rigorous Results (1995). DOI |

| [4] | D. J. Thouless, Exchange in solid 3He and the Heisenberg Hamiltonian (1965). DOI |

| [5] | H. Tasaki, From Nagaoka's ferromagnetism to flat-band ferromagnetism and beyond (1997). arXiv |

| [6] | P. W. Anderson, F. D. M. Haldane, The Symmetries of Fermion Fluids at Low Dimensions (2000). arXiv |

| [7] | A. Mielke, Exact ground states for the Hubbard model on the Kagome lattice (1992). DOI |

| [8] | A. Mielke, H. Tasaki. Ferromagnetism in the Hubbard model (1993). DOI |