Taming Edgy Currents by Disorder

This small note is an expanded version of my final writeup for PHYSICS 268AR that I took my first semester. I thank Rahul Sahay for intensive discussions on related experiments and Tomohiro Soejima for proofreading.

Hall Conductance from Edges

We all know that in quantum Hall-like systems, edge states dominate the transport signatures. How do we see that?

Let us focus on the simplest states: the \(|\nu|=1/m\) Laughlin states. The transport signatures are:

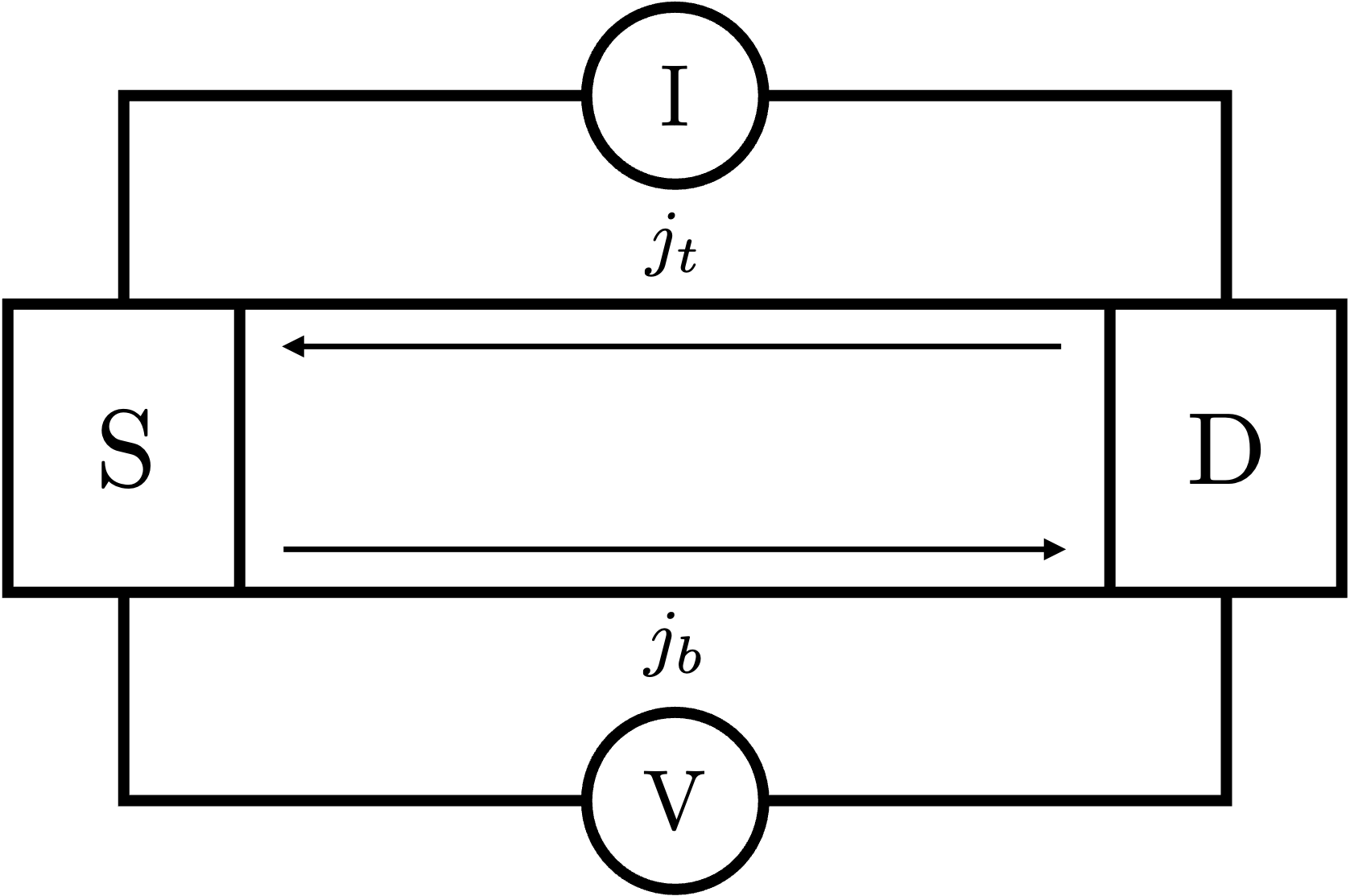

\[G^{2T} = |G_H^{4T}| = \frac{e^2}{mh},\]in which \(G=I/V\) is the conductance. For two terminal we employ the following geometry:

Two terminal conductance: bottom edge

The two terminal conductance calculation is easy to perform, and we can actually derive the four terminal conductance from the two terminal conductance. We begin the calculation by writing down the edge theory for the bottom edge. The edge theory of such states is a simple chiral Luttinger liquid (note that here I am writing down the Minkowski action!):

\[S = \frac{m}{4\pi}\int dxdt \ \partial_x\phi(\partial_t+v\partial_x)\phi\]The dictionary between \(\phi\) and physical quantities is:

\[\rho(x) = \frac{e}{2\pi}\partial_x \phi,\quad j(x) = \frac{e}{2\pi}\partial_t \phi.\]In this sense, the second term \(v(\partial_x\phi)^2=v\rho^2\) corresponds to the interaction term, which we are familar with in the language of bosonization. We can now calculate the response along the edge based on linear response:

\[j(x) = \int dx' D^R(x-x', \omega\to 0)V(x')\]in which \(D^R\) is the retarded response function and \(V(x)\) is the potential. \(D^R\) can be expressed as

\[D^R(x-x', \omega) = -\frac{i}{\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt e^{-i\omega t}\left\langle \left[j(x,0),\rho(x', t)\right] \right\rangle.\]To compute the commutator, we first solve for the canonical momentum:

\[\pi(x) = \frac{\delta S}{\delta(\partial_t \phi)} = \frac{m}{2\pi}\partial_x\phi(x),\]which means that

\[[\partial_x\phi(x), \phi(x')] = \frac{2\pi i}{m}\delta(x-x').\]We can proceed by solving for the normal modes, i.e. the solution to the equation of motion, which are given by

\[\partial_x(\partial_t+v\partial_x)\phi=0.\]Assuming that \(\phi(x,t) = \int \frac{dq}{2\pi }\phi_q e^{i(qx-\omega(q)t)},\) we obtain

\[\omega(q) = vq.\]We can thus rewrite

\[\phi(x,t) = \int \frac{dq}{2\pi }\phi_q e^{iq(x-vt)}\]From this, we see that indeed the theory is describing a chiral boson.

Using the definition of the canonical momentum above, we can derive

\[\pi_q = \frac{m}{2\pi}(-iq)\phi_q, \quad [\pi_q, \phi_q]=-i.\]Thus, we may compute the retarded respose function:

\[ \begin{aligned} D^R(x-x', \omega)&=-\frac{i}{\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt e^{-i\omega t}\left\langle \left[j(x,0),\rho(x', t)\right] \right\rangle\\ &=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt e^{-i\omega t}\left\langle \left[\partial_t\phi(x,0), \partial_x'\phi(x',t)\right] \right\rangle\\ &=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt e^{-i\omega t}\int \frac{dq}{2\pi}\frac{dq'}{2\pi}e^{i(qx-q'x'+vq't)}\left\langle \left[\phi_q(-ivq), \phi_{-q'}(-iq')\right] \right\rangle\\ &=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt e^{-i\omega t}\int \frac{dq}{2\pi}e^{iq((x-x')+vt)}\frac{2\pi(-ivq) i}{m}\\ &=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2m\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt e^{-i\omega t}\int dq\ e^{iq((x-x')+vt)}vq \end{aligned} \]We will ensure convergence by introducing \(\omega = \omega+i\epsilon^+\), s.t. \(e^{-i(\omega+i\epsilon^+)t}\) at \(t=-\infty\) is convergent:

\[ \begin{aligned} D^R(x-x', \omega)&=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2m\hbar}\int_{-\infty}^0 dt \ e^{-i(\omega+i\epsilon^+) t}\int dq\ e^{iq((x-x')+vt)}vq\\ &=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2m\hbar}\int dq\frac{e^{iq(x-x')}vq}{\epsilon^+-i\omega+ivq}\\ &=-\frac{i e^2}{(2\pi)^2m\hbar}(2\pi i)\Theta(x-x') \frac{-i\omega}{v} e^{i(\omega+i\epsilon^+)(x-x')/v}\\ &=-\frac{ie^2}{mh}\frac{\omega}{v}e^{i(\omega+i\epsilon^+)(x-x')/v}\Theta(x-x') \end{aligned} \]Plugging this into the linear response equation (for example, at \(x=0\)), we soon obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} j(0) &= -\frac{ie^2}{mh}\frac{\omega}{v}\int_{-\infty}^0 dx' e^{(\epsilon^+-i\omega)x'/v}V(x')\\ &\approx -\frac{ie^2}{mh}\frac{\omega}{v} \frac{V(-\infty)}{(\epsilon^+ - i\omega)/v}\\ & = \frac{e^2}{mh} V(-\infty) \end{aligned} \]In the second line, we assumed that the integral will be dominated by \(x'\) large and negative. In the third line, we have taken the limit where \(\epsilon^+\) goes to \(0\) first, and then \(\omega\to 0\). (Sketch of proof: write \(V(x')\) as a fourier sum; using the above sequence of limits, prove that only \(V_{\omega=0}\) remains, and is equal to \(V(-\infty)\).)

Two terminal conductance: both edges

In the above calculation, we have performed the calculation for one edge only. In reality, there is both a top and a bottom edge. Performing the same calculation for the top edge gives us a contribution of \(j_t(0) = -\frac{e^2}{mh}V(\infty)\). Assuming that the edges run parallel, we simply add up their current contributions. Further denoting \(V_L=V(-\infty), V_R=V(\infty)\), we obtain

\[j(0) = j_b(0)+j_t(0) = \frac{e^2}{mh}(V_L-V_R)\]which means that

\[G^{2T} =\frac{e^2}{mh}\]the expected value.

Four terminal conductance: Landauer-Buttiker

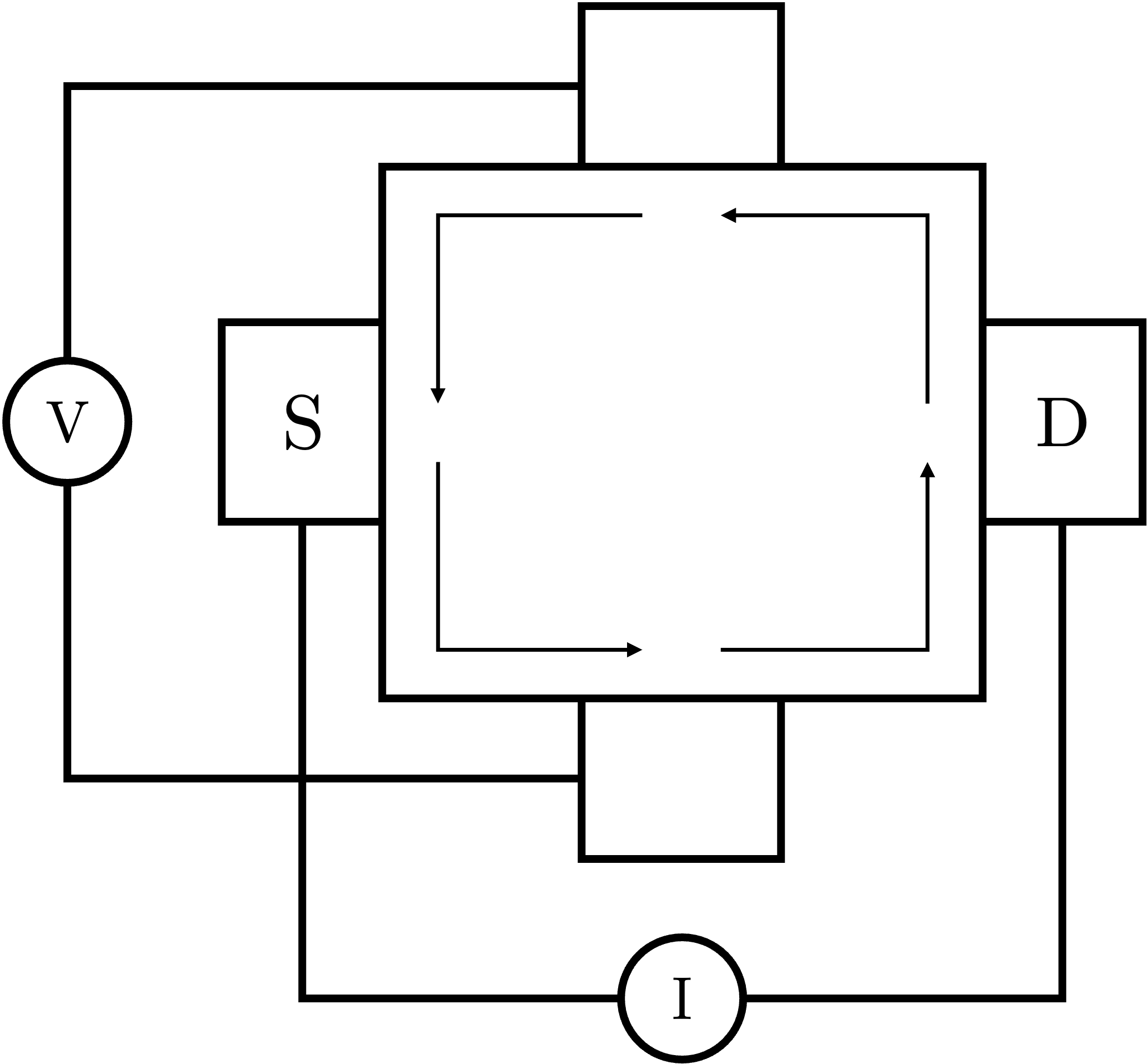

To compute the four terminal conductance one needs to study the geometry a bit better:

The measurement is performed such that there are four leads, namely top, right, bottom, and left (\(i=1\) through \(4\)). A current \(I\) is passed through the left lead to the right lead. Maintaining the current through the top and bottom leads to be \(0\), we measure the voltage difference \(V_{tb}\). The four terminal conductance is computed as

\[G_{H}^{4T} = \frac{I}{V_{tb}}.\]Given that transport along the edges are ballistic, one can employ the Landauer-Buttiker formalism to compute the conductance:

\[ I_i = \sum_{j} G_{ij} V_j \]in which \(I_i\) is the current flowing into lead \(I\), \(G_{ij}\) is the ballistic conductance from lead \(j\) to lead \(i\), and \(V_j\) is the voltage of lead \(j\). Given the geometry above, the conductance matrix elements can be written as

\[ G_{ij}=G^{2T}\delta_{i+1,j}, \]where the delta function is understood mod \(4\). Given the current vector \(I=(0,-I,0,I)\), one can solve that \(G_{H}^{4T} = G^{2T}.\)

The paradox: wrong conductance

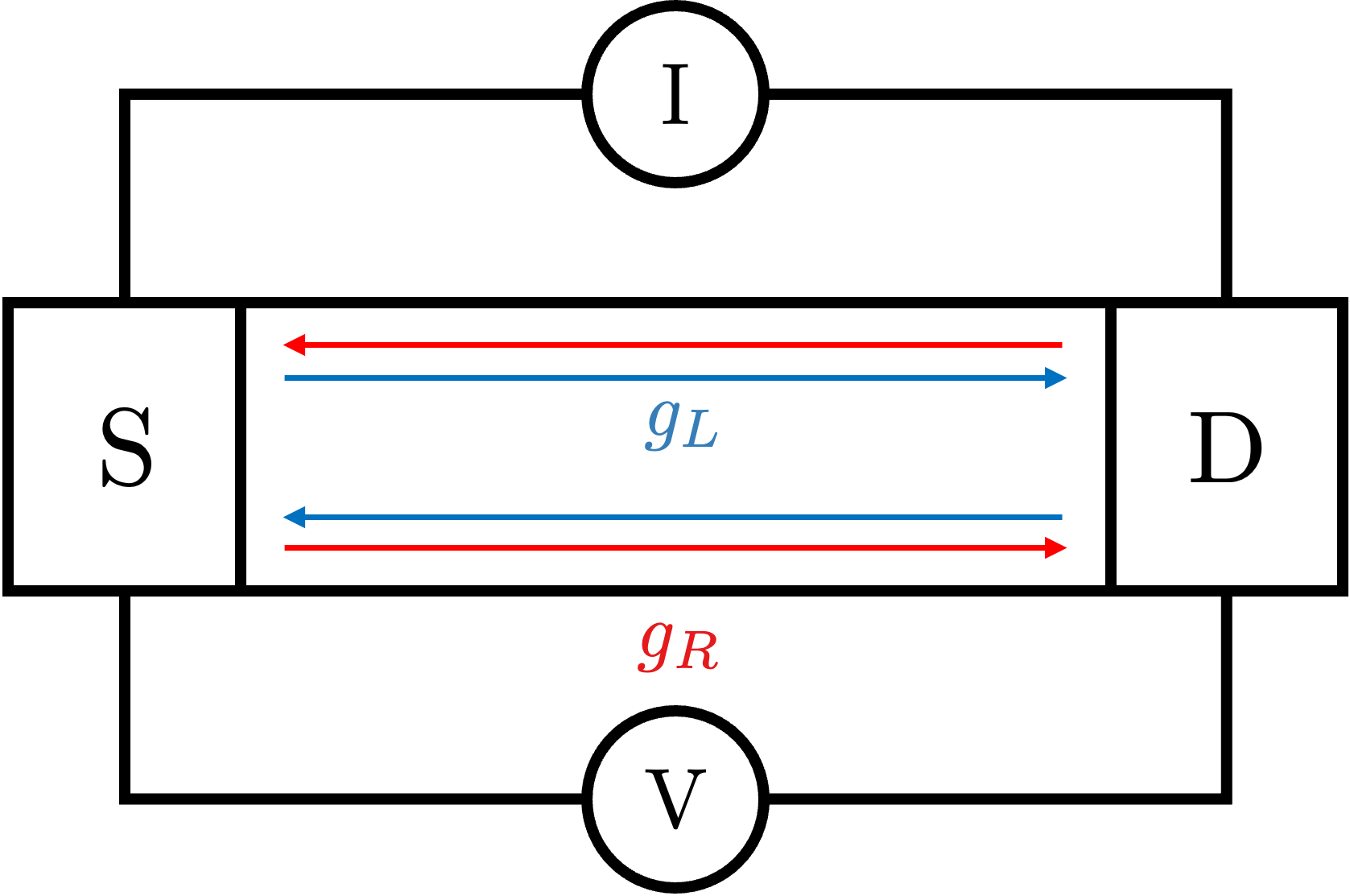

This fantastic scenario is immediately destroyed when there are anti-chiral edge modes. For concreteness, let us imagine the \(\nu=2/3\) quantum Hall state, which one can naively imagine to be a \(\nu=1\) state with a charge \(e\) chiral edge mode stacked with a \(\nu=-1/3\) state (my understanding: charge \(e\) electrons in a \(1/3\) Laughlin state with the opposite magnetic field) with a charge \(e/3\) anti-chiral edge mode. We can understand it simply by looking at the two-terminal conductance with the following geometry:

The two edge modes have \(g_R = e^2/h\) and \(g_L=e^2/3h\) here. Although we expect the correct conductance to be \(G^{2T}=g_L-g_R = 2e^2/3h\), a simple calculation shows that this is not the case. Indeed, for the bottom edge we have

\[j_b = g_RV_L - g_LV_R,\]and for the top edge we have

\[j_t = g_LV_L - g_RV_R.\]Summing up, we obtain

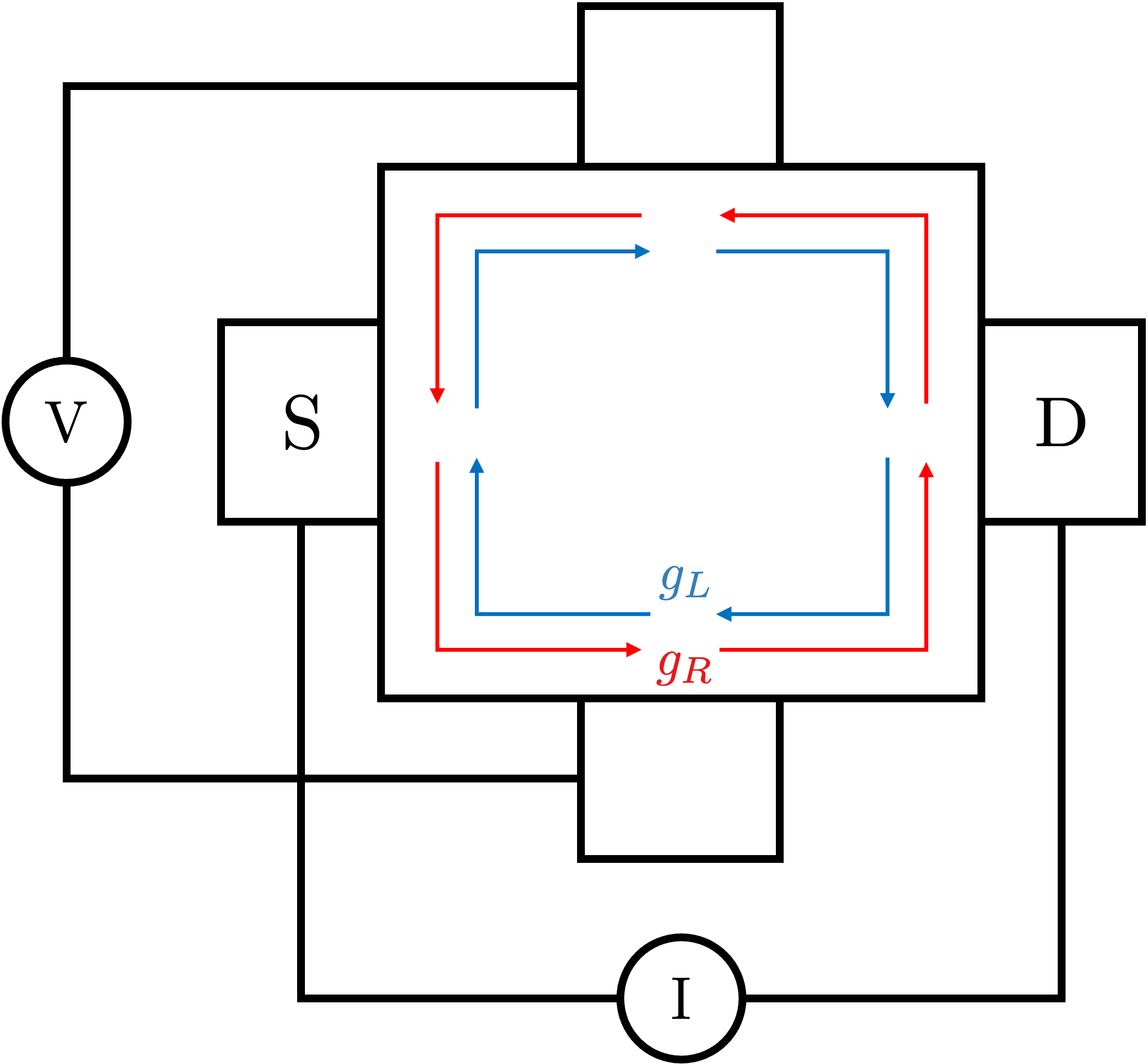

\[G^{2H} = g_L+g_R!\]One can also check that the four terminal Hall conductance is also not correct from the following geometry:

We employ the Landauer-Buttiker formalism, this time with the conductance matrix

\[ G_{ij}=g_R\delta_{i+1,j}+g_L\delta_{i-1, j}, \]where again the delta functions are understood mod \(4\). From this, we can solve for the four terminal conductance to be

\[ G_H^{4T} = \frac{g_R^2+g_L^2}{g_R-g_L}. \]Thus, this formula can only be correct if the edge is perfectly chiral!

This paradox was first observed by Kane, Fisher and Polchinski in Ref. [1]. Below we discuss their solution to this paradox.

Disorder at play

What the authors realized is that the edge is unfortunately disordered. Disorder acts like a local potential and can introduce scattering from one edge mode into another edge mode. Particularly, they write down the following (Minkowski) action for the bottom edge:

\[ S = S_{0}+S_1 \]where

\[ S_{0} = -\frac{1}{4\pi}\int dxdt \ [ \partial_x\phi_1(\partial_t+v_1\partial_x)\phi_1 +3\partial_x\phi_2(-\partial_t+v_2\partial_x)\phi_2+2v_{12}\partial_x\phi_1\partial_x\phi_2] \]and

\[ S_1 = \int dx dt \ \xi(x) e^{i(\phi_1+3\phi_2)}+c.c. \]Again, we remind ourselves of the dictionary:

\[ \rho(x) = \frac{e}{2\pi}\partial_x(\phi_1+\phi_2), \quad j(x) = \frac{e}{2\pi}\partial_t(\phi_1+\phi_2). \]Furthermore, \(e^{i\phi_1}\) creates a charge \(e\) particle in mode \(\phi_1\), whereas \(e^{-i\phi_2}\) creates a charge \(e/3\) particle in mode \(\phi_2\). (This can be seen from the commutation relations of \([\partial_x\phi_i, \phi_i]\) and computing the charge density created by \(e^{\pm i \phi_i}\).) Thus, indeed \(S_1\) describes a disorder potential induced process that tunnels \(3\) \(e/3\) particles from \(\phi_2\) to an \(e\) particle in \(\phi_1\). \(\xi(x)\) describes a Gaussian random variable with short range correlations:

\[ \left\langle \xi^*(x)\xi(x') \right\rangle=W\delta(x-x'). \]Indeed if we choose to use the Luttinger liquid action \(S_0\) alone, we would have obtained

\[ G^{2T}=\frac{2}{3}\Delta \frac{e^2}{h}, \quad G_H^{4T} = \frac{1}{3}(1+\Delta^2)\frac{e^2}{h}, \quad \Delta = \frac{2-\sqrt{3}c}{1-c^2}, \]where \(c=2v_{12}/\sqrt{3}(v_1+v_2)\). The interactions \(v_{12}\) strongly modify both conductances – their robustness in experimental measurements thus suggest that taking \(S_0\) only is not the best choice.

How important is the disorder?

Given the effective action \(S\), one may compute an effective action by integrating out \(\xi\). This means that there will effectively be a term

\[ S_2 = W\int dx dt dt' \ O(x,t)O^\dagger(x,t') \]where \(O=e^{i(\phi_1+3\phi_2)}\). We can then ask naively what the scaling dimension is for the operator \(O O^\dagger\), which amounts to asking for the scaling dimension of \(O\). If this term is irrelevant, then perhaps we can throw it away and argue that disorders merely act as an irrelevant perturbation.

The way to compute this scaling dimension is to calculate its correlation function \(\left\langle O(x,t)O(0,0) \right\rangle\). Given that the bare action \(S_0\) is quadratic, we have

\[ \begin{aligned} \left\langle O(x,t)O(0,0) \right\rangle& = \left\langle e^{i(\phi_1+3\phi_2)(x,t)}e^{-i(\phi_1+3\phi_2)(0,0)} \right\rangle\\ &= e^{-\left\langle ((\phi_1+3\phi_2)(x,t)-(\phi_1+3\phi_2)(0,0))^2 \right\rangle/2} \end{aligned} \]in which the second term is due to the Wick's theorem of the free fields \(\phi_1\) and \(\phi_2\).

The problem is thus reduced to computing the correlation function

\[ \begin{aligned} C(x,t)&=\left\langle ((\phi_1+3\phi_2)(x,t)-(\phi_1+3\phi_2)(0,0))^2 \right\rangle\\ &= 2\int \frac{dq }{2\pi}\frac{d\omega}{2\pi}\left\langle (\phi_1+3\phi_2)(q,\omega)(\phi_1+3\phi_2)(-q,-\omega) \right\rangle(1-e^{i(qx-\omega t)})\\ &= 4\int_0^\infty \frac{dq }{2\pi} \int\frac{d\omega}{2\pi}A(q,\omega) (1-e^{i(qx-\omega t)}), \end{aligned} \]in which \(A(q,\omega)=v^T \Sigma^{-1}(q, \omega) v\), \(v = (1,3)^T\) and \(\Sigma\) is related to the Minkowski action:

\[ S_0= \int_0^\infty \frac{dq }{2\pi} \int\frac{d\omega}{2\pi} \Phi^T(-q,-\omega) \Sigma(q,\omega) \Phi(q,\omega)\]in which \(\Phi=(\phi_1,\phi_2)^T\), and

\[\Sigma(q,\omega) = \frac{iq}{2\pi}\begin{pmatrix}\omega-v_1 q & -v_{12}q\\ -v_{12} q & -3(\omega+v_2 q)\end{pmatrix}.\]Now, we may massage \(A(q,\omega)\):

\[ \begin{aligned} A(q, \omega)&=\frac{2\pi}{i} \frac{3q(3 v_1+v_2-2v_{12})-6\omega}{q(3\omega^2+3q(v_2-v_1)\omega)+q^2(v_{12}^2-3 v_1v_2)}\\ &= \frac{2\pi}{i} \frac{q(3 v_1+v_2-2v_{12})-2\omega}{q(\omega - v_+ q)(\omega - v_- q)}, \end{aligned} \]where

\[ v_{\pm} = \frac{v_1-v_2}{2} \pm\frac{(v_1+v_2)}{2} \sqrt{1-c^2},\quad c=\frac{2v_{12}}{\sqrt{3}(v_1+v_2)}. \]With this, we may use the Cauchy's residue theorem:

\[ \begin{aligned} C(x,t)&=2\int_0^\infty dq \left[\frac{\Delta_+}{q} (1-e^{i q (\omega-v_+ t)})+\frac{\Delta_-}{q} (1-e^{i q (\omega-v_+ t)})\right] \end{aligned} \]where

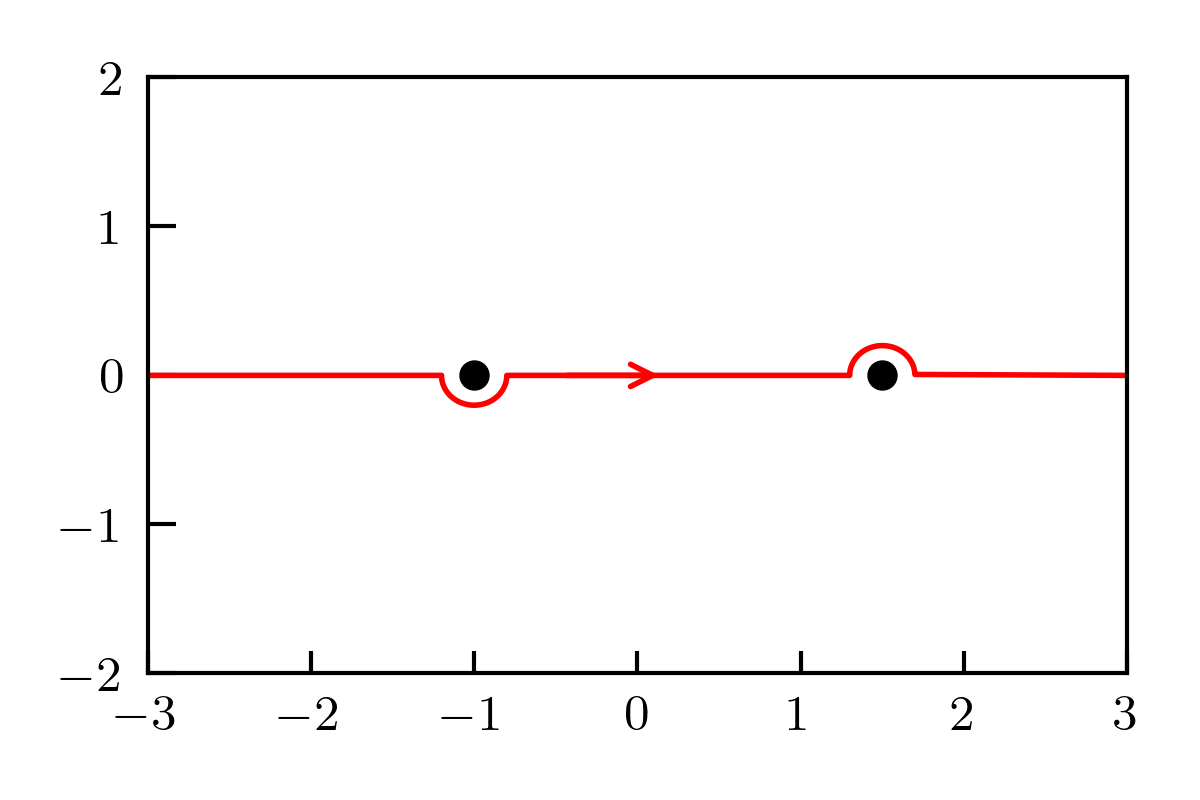

\[ \Delta_{\pm} = \pm q \ \left.\textrm{Res}\left(\frac{q(3 v_1+v_2-2v_{12})-2\omega}{q(\omega - v_+ q)(\omega - v_- q)}\right)\right|_{\omega=v_{\pm}q}. \]The sign in front of the residue is because of the contour we chose:

which is consistent with the contour used in Wick's theorem.

Thus, we obtain:

\[ \Delta_{\pm} = \Delta \mp 1, \quad \Delta = \frac{2-\sqrt{3}c}{\sqrt{1-c^2}}. \]which agrees with the definition of \(\Delta\) above. Now, we can finally evaluate the correlation function \(C(x,t)\). Before this, we can evaluate the following (divergent) auxiliary integral:

\[ \begin{aligned} F(z) &= \int_0^\infty\frac{dq}{q}(1-e^{iqz})\\ &\approx \int_0^{a^{-1}} \frac{dq}{q} (1-e^{iqz}) \approx \log\left(\frac{z}{a}\right)+C \end{aligned} \]which can be obtained by differentiating and integrating with respect to \(z\) (I thank Ophelia Sommer and Patrick Ledwith for pointing this out to me). Thus, we can finally evaluate the desired correlation function:

\[ \begin{aligned} \left\langle O(x,t)O(0,0) \right\rangle&= e^{-C(x,t)/2}\\ &\propto \frac{1}{(x-v_+ t)^{\Delta_+}(x-v_-t)^{\Delta_-}}. \end{aligned} \]Thus, we conclude that the scaling dimension of \(O\) is \(\frac{\Delta_++\Delta_-}{2}=\Delta\).

In this case, the scaling dimension for \(W\) is thus \(3-2\Delta\). When \(\Delta\) is less than \(3/2\), this term will become strongly relevant.

Note that this effective interaction can only be induced by disorder given that it is nonlocal in time. We also note that \(O\) the operator alone carries nonzero momentum and thus cannot be added to the action without translation symmetry breaking. I thank Ruben Verresen for pointing this out to me in the group meeting.

The disorder-dominated phase

One might think that the strongly coupled phase is not solvable. This is shown to not be the case. We first define new variables

\[ \phi_\rho = \sqrt{\frac{3}{2}}(\phi_1+\phi_2),\quad\phi_\sigma=\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}}(\phi_1+3\phi_2). \]\(\phi_\rho\) is the charge mode; for example, \(\rho = \sqrt{2/3} e\partial_x\phi_\rho/2\pi\). \(\phi_\sigma\) is the neutral mode. One can rewrite

\[ \begin{aligned} S &= S_\rho + S_\sigma + S_{pert},\\ S_\rho &= -\frac{1}{4\pi}\int_{x,t} \ \partial_x\phi_\rho(\partial_t+v_\rho\partial_x)\phi_\rho,\\ S_\sigma &= -\frac{1}{4\pi}\int_{x,t} \ \partial_x\phi_\sigma(-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\phi_\sigma + \int_{x,t}[\xi(x)e^{i\sqrt{2}\phi_\sigma}+c.c.],\\ S_{pert} &= v \int_{x,t} \partial_x\phi_\rho\partial_x\phi_\sigma. \end{aligned} \]The parameters are

\[ v_\rho = \frac{3v_1+v_2-2v_{12}}{2}, \quad v_\sigma = \frac{v_1+3v_2-2v_{12}}{2}, \quad v = -\frac{3v_1-4v_{12}+3v_2}{\sqrt{3}} \]When \(\Delta\) is close to \(1\), \(c\) is close to \(\sqrt{3}/2\), and thus \(v\approx 0\). In more detail, one can derive

\[ \Delta-1 \approx 8 \left(c-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^2, \frac{v}{v_\rho+v_\sigma} \approx 4\left(c-\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) \Rightarrow v = \sqrt{2}(v_\rho+v_\sigma)\sqrt{\Delta-1}. \]We will now proceed with the following program. We will massage \(S_\sigma\) into a more palatable form such that we can argue that \(v\) is irrelevant. Then, \(\phi_\rho\) and \(\phi_\sigma\) decouple; one can then compute the charge response with \(\phi_\rho\) alone. Since \(\phi_\rho\) is the only charged mode, we can derive that its \(g_R\) is \(2/3\) due to the \(\sqrt{2/3}\) prefactor in the definition of \(\rho\). This means that both the two terminal and four terminal charge responses will be correct if this is true.

Hidden \(SU(2)\) symmetry

Now we note that the action \(-\frac{1}{4\pi}\int_{x,t} \ \partial_x\phi_\sigma(-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\phi_\sigma\) actually describes the neutral sector of a spin-\(1/2\) chiral fermion, with the current algebra given by \(J^{\pm}\sim\psi^\dagger \sigma^{\pm}\psi\sim e^{\pm i\sqrt{2}\phi_\sigma}\), and \(J_z\sim\psi^\dagger \sigma_z \psi\sim\partial_x\phi_\sigma\). To do this more explicitly, we introduce an additional boson \(\chi\) where

\[ S_{\chi} = -\frac{1}{4\pi}\int_{x,t} \ \partial_x\chi(-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\chi. \]To describe the charge sector of the auxiliary fermions. \(\chi\) will not enter any physical observables. Then, we fermionize \(S_{\sigma}+S_{\chi}\) to be describing the fermions \(\psi\):

\[ S_{\psi}=\int_{x,t} i\psi^\dagger (-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\psi + \psi^\dagger (\xi \sigma^+ + \xi^*\sigma^-)\psi, \]in which we identify the two components of \(\psi\) as

\[ \psi_{\pm}=e^{i(\chi\pm\phi_\sigma)/\sqrt{2}}. \]The disorder thus acts as an \(SU(2)\) gauge field that guides the spinor direction of the fermions \(\psi\). We can thus rotate into the gauge in which the spinors do not feel any gauge field:

\[ U(x) = T_x \exp\left[-i\int_{-\infty}^x dx' M(x')\right],\quad M(x) = [\xi(x)\sigma^+ + \xi^*(x)\sigma^-]/v_\sigma. \]In the gauge \(\tilde{\psi} = U(x)\psi(x)\), we obtain

\[ S_{\tilde{\psi}} = \int_{x,t}i\tilde\psi^\dagger (-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\tilde\psi. \]This is thus the full action when \(\Delta =1\) (\(v=0\)): it is described by a charged boson \(\phi_\rho\) and the neutral sector of a spin-\(1/2\) fermion \(\tilde{\psi}\).

Coupling between \(\phi_\rho\) and \(\tilde{\psi}\)

The perturbation term that couples the boson and fermion is

\[ S_{pert} = \frac{v}{4\pi} \int_{x,t} \partial_x\phi_\rho \left(i\tilde\psi^\dagger U(x)\sigma_z U^\dagger(x) \tilde{\psi}\right) \]Given that \(\Delta_{\phi_\rho}=0, \Delta_{\tilde\psi} = 1/2\), we can obtain the scaling dimension for the operator \(O_v = \partial_x\phi_\rho \psi^\dagger\psi\) to be \(2\) – exactly marginal. However, this naive calculation ignores the spatial correlation of \(U(x)\).

Given that \(U(x)\) is basically a random \(SU(2)\) matrix and thus should average to zero, we should consider its quadratic average. Given the delta function correlation of \(\xi\), \(U\) should be delta function correlated as well:

\[ v^2\left\langle U(x)U^\dagger(x') \right\rangle = \tilde{v} \delta(x-x'). \]Thus, the effective action is

\[ S_{eff} \sim \tilde{v}\int_{x,t,t'} (\partial_x\phi_\rho)^2 (\tilde{\psi}^\dagger\tilde{\psi})^2 \]which shows that the coupling \(\tilde{v}\) has dimension \(3-2\Delta_{O_v}=-1\). Hence the term is irrelevant and thus the disorder induced fixed point is stable.

A couple comments are in order, which are kindly pointed out by Patrick Ledwith and Eslam Khalaf. Firstly, although the disorder term is shown to be perturbatively relevant for \(\Delta<3/2\), it is unclear where the IR fixed point will be. The above calculation shows that the \(\Delta=1\) point is perturbatively stable, but it does not establish that for any \(\Delta<3/2\) the theory will flow to \(\Delta=1\). Secondly, although a rewriting of \(S\) in terms of \(\phi_\rho\) and \(\phi_\sigma\) is possible in the clean limit, one would find that \(v\) is marginal and would not flow. This is why disorder induced correlations are important. Thirdly, a more careful analysis of the random couplings between \(\phi_\rho\) and \(\tilde\psi\) based on replica tricks can be found in [2].

Stripping off \(\chi\)

One might worry that the above transformations are not legit, given that an additional degree of freedom, i.e. \(\chi\), corresponding to the \(U(1)\) charge dynamics of \(\psi\), has been added. We will now show that this is not the case.

Let us set \(v\) to zero, i.e. the fixed point. We now study the fermion action \(S_{\tilde{\psi}}\) by re-bosonizing it into charge \(\chi'\) and spin fluctuations \(\phi_\sigma'\) by the formula

\[ \tilde\psi_{\pm}=e^{i(\chi'\pm\phi'_\sigma)/\sqrt{2}}. \]Particularly, for \(\psi\) fermions \(\partial_x\chi = 2\pi \psi^\dagger\psi\); for \(\tilde{\psi}\) fermions \(\partial_x\chi' = 2\pi \tilde\psi^\dagger \tilde\psi\). However, under the \(SU(2)\) transformation \(\psi^\dagger\psi=\tilde\psi^\dagger \tilde\psi\), so morally \(\chi=\chi'\).

Thus, after the bosonization the action becomes

\[ \begin{aligned} S_{\chi'} &= S_{\chi} = -\frac{1}{4\pi}\int_{x,t} \ \partial_x\chi(-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\chi\\ S_{\phi_\sigma'} &= \partial_x\phi_\sigma(-\partial_t+v_\sigma\partial_x)\phi_\sigma \end{aligned} \]Experimental signature

To summarize: strong disorder reconstructs the edge structure of the \(\nu=2/3\) state. It transforms the \(1-1/3\) edge, i.e. a chiral charge \(e\) mode and an anti-chiral charge \(e/3\) mode, to a \(2/3+0\) edge, i.e. a chiral charge \(2e/3\) mode and an anti-chiral charge neutral mode.

Aside from the tunneling experiments, thermal measurements is enough to probe the existence of the neutral mode. Although the neutral mode cannot carry electric charge, it still carries thermal energy. Given that the neutral mode will equilibrate when it goes into the source lead, there will be heat noise near the source lead due to the neutral mode. The charged mode will create electric and thermal noise near the drain lead. This has been measured by Ref. [3].

References

| [1] | Randomness at the edge: Theory of quantum Hall transport at filling \(\nu=2/3\) (1994). DOI |

| [2] | Transport in a disordered \(\nu=2/3\) fractional quantum Hall junction (2017). DOI |

| [3] | Observation of ballistic upstream modes at fractional quantum Hall edges of graphene (2022). DOI |